By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

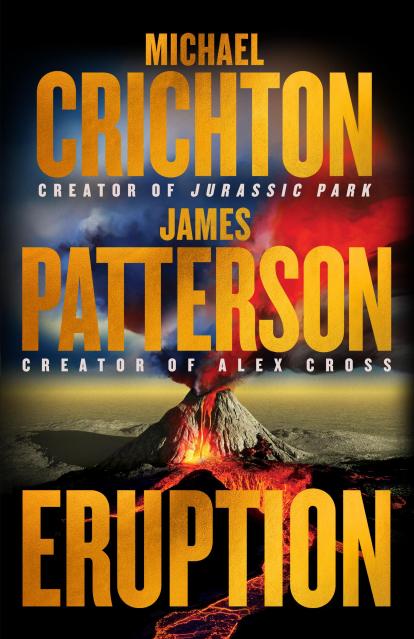

Eruption

Instant #1 New York Times Bestseller

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$15.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

Also available from:

The biggest thriller of the year: A history-making eruption is about to destroy the Big Island of Hawaii. But a secret held for decades by the US military is far more terrifying than any volcano.

“The book is a classic summer beach read…Eruption will revive the art of speed-reading…told with a singular voice that is a compelling amalgam of the two writers.”—USA Today

“Eruption is an epic thriller…fast-paced and deeply considered…a cinematic story rooted in science and infused with plenty of heart, tackling big themes like love and loss.”

–Time

The master of the techno-blockbuster joins forces with the master of the modern thriller to create the most anticipated mega bestseller in years.

Michael Crichton, creator of Jurassic Park, ER, Twister, and Westworld, had a passion project he’d been pursuing for years, ahead of his untimely passing in 2008. Knowing how special it was, his wife, Sherri Crichton, held back his notes and the partial manuscript until she found the right author to complete it: James Patterson, the world’s most popular storyteller.

“Red-hot storytelling… The action scenes will make readers’ eyes pop as the tension continues to build." –Kirkus, starred review

“Explosive…the summer’s ultimate literary mashup.” —Washington Post

"Takes readers on a thrilling journey." —BBC

"Beachbag-ready." —Boston Globe

“A seismic publishing event…all the elements of a summer blockbuster…it’s a thrill and the pages practically turn themselves.” —Associated Press

“Eruption is this summer’s literary version of a blockbuster action movie.” –Los Angeles Times

"Breakneck and plausible." —Publishers Weekly

-

“Eruption is this summer’s literary version of a blockbuster action movie.”Los Angeles Times

-

“Eruption is an epic thriller…fast-paced and deeply considered…a cinematic story rooted in science and infused with plenty of heart, tackling big themes like love and loss.”Time

-

“Explosive … the summer’s ultimate literary mashup."Washington Post

- On Sale

- Jun 3, 2024

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316565080

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

What's Inside

PROLOGUE

“The volcanoes aren’t going to explode today, are they?” a little girl asked, her large brown eyes pinned to the twin peaks: Mauna Loa, the largest active volcano in the world, and Mauna Kea, which hadn’t erupted in more than four thousand years.

“If they even think about it,” Rachel Sherrill said, “we’re going to build a dome over them like we do with those new football stadiums. We’ll see how they like that next time they try to blow off a little steam.”

But not all the fifth-graders were laughing at the joke told by the chief botanist of the Hilo Botanical Gardens.

“Why is this tree turning black, Ms. Sherrill?” an inquisitive boy with wire-rimmed glasses sliding down his nose called out.

Christopher had wandered away from the group and was standing in front of a small grove of banyan trees about thirty yards across the lawn.

In the next instant, they all heard the jolting crash of what sounded like distant thunder. Rachel wondered, the way newcomers to Hawai‘i always wondered, Is a big storm coming or is this the start of an eruption?

As most of the children stared up at the sky, Rachel hurried over to the studious, bespectacled boy who was looking at the banyan trees with a concerned expression on his face.

“Now, Christopher,” Rachel said when she got to him, “you know I promised to answer every last one of your questions—”

The rest of what she’d been about to say collapsed in her throat. She saw what Christopher was seeing—she just couldn’t believe her eyes.

It wasn’t just that the three banyan trees closest to her had turned black. Rachel could actually see inky, pimpled blackness spreading like an oil spill, some terrible stain, except that the darkness was climbing up the trees. It was like some sort of upside-down lava flow from one of the volcanoes, but the lava was defying gravity, not to mention everything Rachel Sherrill knew about plant and tree diseases.

She bent low to the ground and saw suspicious dark spots leading up to the tree, like the tracks of some mythical round-footed animal. Rachel knelt down and felt the spots. The grass wasn’t moist. Actually, the blades felt like the bristles on a wire brush.

None of the blackness had been here yesterday.

She touched the bark of another infected tree. It flaked and turned to dust. She jerked her hand away and saw what looked like a black ink stain on her fingers.

“These trees must have gotten sick,” she said.

As she ushered the kids back to the main building, her mind raced to come up with possible explanations for what she’d just witnessed. But nothing made sense. Rachel had never seen or

read about anything like this. It wasn’t the result of the vampire bugs that could eat away at banyan trees if left unchecked. Or of Roundup, the herbicide that the groundskeepers used overzealously on the thirty acres of park that stretched all the way to Hilo Bay. Rachel had always considered herbicides a necessary evil—like first dates. This was something else. Something dark, maybe even dangerous, a mystery she had to solve.

When the children were in the cafeteria, Rachel ran to her office. She checked in with her boss, then made a phone call to Ted Murray, an ex-boyfriend at Stanford who had recommended her for this job and convinced her to take it and who now worked for the Army Corps of Engineers at the Military Reserve.

She explained what she had seen, knowing she was talking too quickly, her words falling over each other as they came spilling out of her mouth.

“On it,” Murray said. “I’ll get some people out there as soon as I can. And don’t panic.”

“Ted, you know I don’t scare very easily.”

“Tell me about it,” Murray said. “I know from my own personal experience that you’re the one usually doing the scaring.”

She hung up, knowing she was scared, the worst fear of all for her: not knowing. While the children continued noisily eating lunch, she put on the running shoes she kept under her desk and ran all the way back to the banyan grove.

There were more blackened trees when she got there, the stain creeping up from distinctive aerial roots that stretched out like gnarled gray fingers.

Rachel Sherrill tentatively touched one of the trees. It felt like a hot stove. She checked her fingertips to make sure she hadn’t singed them.

A voice came crackling over the loudspeakers—Rachel Sherrill’s boss, Theo Nakamura, telling visitors to evacuate the botanical gardens immediately.

“This is not a drill,” Theo said. “This is for the safety of everyone on the grounds. That includes all park personnel. Everyone, please, out of the park.”

Within seconds, park visitors started coming at Rachel hard. The grounds were more crowded than she had thought. Mothers ran as they pushed strollers ahead of them. Children ran ahead of their parents. A teen on a bike swerved to avoid a child, went down, got up cursing, climbed back on his bike, and kept going. Smoke was suddenly everywhere.

“It could be a volcano!” Rachel heard a young woman yell.

Rachel saw two army jeeps parked outside the distant banyan grove. Another jeep roared past her; Ted Murray was at the wheel. She shouted his name but Murray, who probably couldn’t hear her over the chaos, didn’t turn around.

Murray’s jeep stopped, and soldiers jumped out. Murray directed them to form a perimeter around the entrance to the grove and ensure that the park visitors kept moving out.

Rachel ran toward the banyan grove. Another jeep pulled up in front of her and a soldier stepped out.

“You’re heading in the wrong direction,” the soldier said.

“You—you don’t understand,” she stammered. “Those —they’re my trees.”

“I don’t want to have to tell you again, ma’am.”

Rachel Sherrill heard a chopper engine; she looked up and saw a helicopter come out of the clouds from behind the twin peaks. Saw it touch down and saw its doors open. Men in hazmat suits, tanks strapped to their backs, came out carrying extinguishers labeled cold fire. They pointed them like handguns and ran toward the trees.

Her trees.

Rachel ran toward them and toward the fire.

In that same moment she heard another crash from the sky, and this time she knew for sure it wasn’t a coming storm.

Please not today, she thought.

•••

CHAPTERS 2–5

Lono leaned in and spoke in a low voice, even though no one was close enough to hear him: “Is there gonna be an eruption, Mac?”

John MacGregor reached for the door of his truck. On it was a white circle with the letters HVO in the center and the words Hawaiian Volcano Observatory on the outside. But then he stopped.

Lono looked up at him, eyes more troubled than before, a kid trying hard not to act scared but unable to carry it off. Lono said, “You can tell me if there is.”

Mac didn’t want to say anything that would scare him even more, but he didn’t want to lie to him either. “Come with me to my press conference,” he said, forcing a smile. “You might learn something.”

“Learning all the time from you, Mac man,” the boy said.

Of all the kids, Lono was the one Mac had most aggressively encouraged to become an intern at the observatory, recognizing from the start how fiercely bright this boy was despite average grades in school.

“You live here, you always worry about the big one,” Mac said, “whether it’s your job or not.”

MacGregor got in the truck, started the engine, and drove off toward the mountain, thinking about all the things he hadn’t said to Lono Akani, primarily how worried he actually was—and for good reason. Mauna Loa was just days away from its most violent eruption in a century, and John MacGregor, the geologist who headed the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, knew that and was about to announce it to the press. He’d always known this day would come, probably sooner rather than later. Now here it was.

Mac drove fast.

Jenny Kimura was waiting for him. “We’re ready, Mac.”

“They’re all here?”

“Honolulu crew just arrived.” Jenny was thirty-two, the scientist in charge of the lab. She was a Honolulu native with a PhD in earth and planetary sciences from Yale.

Mac saw the other buildings of the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, all connected by tin walkways. The HVO was built on the rim of the Kīlauea caldera, where no lava was flowing in the crater these days. Sure enough, there was now steam coming out of the summit crater of Mauna Loa, proof that he’d been right—the eruption was only days away. He felt as if a ticking clock had begun its countdown.

“Good afternoon,” he said into the microphone. “I’m John MacGregor, scientist in charge of the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory. Thank you all for coming today.”

He turned to the map. “As you know, this observatory monitors six volcanoes—the undersea volcano Kama‘ehuakanaloa, formerly Lō‘ihi; Haleakalā, on Maui; plus four on the Big Island of Hawai‘i, including the two active volcanoes, Kīlauea, a relatively small volcano that has been continuously active for over forty years, and Mauna Loa, the largest volcano in the world, which erupted in 2022 but has not had a major eruption since 1984.”

“Today,” MacGregor said, “I am announcing an imminent eruption of Mauna Loa.”

The photographers’ strobe lights were like flashes of lightning. MacGregor blinked away the white spots in front of his eyes, cleared his throat again, and kept going. He’d probably only imagined that the television lights had just gotten brighter.

“We expect this to be a fairly large eruption,” he said, “and we expect that it will come within the next two weeks, perhaps much sooner than that.”

Wendy Watanabe from one of the Honolulu TV stations raised a hand. “At what point will HVO raise the volcano alert level?”

“While Mauna Loa is at elevated unrest, the level remains at advisory/yellow,” MacGregor said. “We remain focused on the northeast rift zone.”

Everybody else on the HVO staff had seen famous eruptions on videotape.

MacGregor had been there. If he was acting this quickly and decisively now, he had his reasons. He’d been there. He knew.

He also knew enough not to explain in detail that HVO was tracking the biggest eruption in a century—that would only have caused a panic, no matter which side of the volcano was going to blow.

There was one other thing that Mac knew and Jenny knew but the media didn’t.

John MacGregor was lying his ass off.

He knew exactly when the eruption was coming, and it wasn’t two weeks or even one.

Five days.

And counting.

•••

CHAPTERS 7–13

A helicopter appeared in the window of the data room at the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, frighteningly close and low; it rushed past them and swooped down into the caldera.

“Sweet Jesus!” lead programmer Kenny Wong yelled, running to the window to get a better look.

“Get the tail number,” John MacGregor, scientist in charge of HVO, snapped, “and call Hilo ASAP. Whoever that idiot is, he’s going to give one of the tourists a haircut!” He went to the window and watched as the helicopter dropped low and thumped its way across the smoking plain of the caldera. The pilot couldn’t be more than twenty feet above the ground.

Beside MacGregor, Kenny watched through binoculars. “It’s Paradise Helicopters,” he said, sounding puzzled. Paradise Helicopters was a reputable operation based in Hilo. Their pilots ferried tourists over the volcanic fields and up the coast to Kohala to look at the waterfalls.

Mac shook his head. “They know there’s a fifteen-hundred-foot limit everywhere in the park. What the hell are they doing?”

The helicopter swung back and slowly circled the far edge of the caldera, nearly brushing the smoking vertical walls.

The woman in charge of the volcano alert levels, Pia Wilson, cupped her hand over the phone. “I got Paradise Helicopters. They say they’re not flying. They leased that one to Jake.”

“Is there any news at the moment I might like?” Mac said.

“With Jake at the controls, there is no good news,” Kenny said.

“Apparently Jake’s got a cameraman from CBS with him, some stringer from Hilo,” Pia said. “The guy’s pushing for exclusive footage of the new eruption.”

“Hey, Mac? You’re not going to believe this.” She flicked on all the remote monitors at the main video panel to show the eastern flank of Kīlauea. “The pilot just flew into the eastern lake at the summit of Kīlauea.”

MacGregor sat down in front of the monitors. Four miles away, the black cinder cone of Pu‘u‘ō‘ō —the Hawaiian name meant “Hill of the Digging Stick” —rose three hundred feet high on the east flank. That cone had been a center of volcanic activity since it erupted in 1983, spitting a fountain of lava two thousand feet into the air. The eruption continued all year, producing enormous quantities of lava that flowed for eight miles down to the ocean. Along the way, it had buried the entire town of Kalapana, destroyed two hundred houses, and filled in a large bay at Kaimūī, where the lava poured steaming into the sea. The activity from Pu‘u‘ō‘ō went on for thirty-five years—one of the longest continuous volcanic eruptions in recorded history—ending only when the crater collapsed in 2018.

Tourist helicopters scoured the area looking for a new place to take pictures, and pilots discovered a lake that had opened to the east of the collapsed crater. Hot lava bubbled and slapped in incandescent waves against the sides of a smaller cone. Occasionally the lava would fountain fifty feet into the air above the glowing surface. But the crater containing the eastern lake was only about a hundred yards in diameter—much too narrow to descend into.

Helicopters never went inside it.

Until now.

MacGregor said, “Do we know gas levels down in there?” Near the lava lake, there would be high concentrations of sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide. MacGregor squinted at his monitor.

“Can you see if the pilot’s got oxygen? ’Cause the cameraman sure doesn’t. Both these idiots could pass out if they stay there.”

“Or the engine could quit,” Kenny said. He shook his head. “Helicopter engines need air. And there’s not a lot of air down there.”

Jenny Kimura, head lab scientist in charge of the lab, said, “They’re leaving now, Mac.”

As they watched, the helicopter began to rise. They saw the cameraman turn and raise an angry fist at Jake Rogers. Clearly he didn’t want to leave.

That meant Rogers’s passenger was even more reckless than he was.

“Go,” MacGregor said to the screen as if Jake Rogers could hear him. “You’ve been lucky, Jake. Just go.”

The helicopter rose faster. The cameraman slammed the door angrily. The helicopter began to turn as it reached the crater rim.

“Now we’ll see if they make it through the thermals,” MacGregor said.

Suddenly there was a bright flash of light, and the helicopter swung and seemed to flip onto its side. It spun laterally across the interior and slammed into the far wall of the crater, raising a tremendous cloud of ash that obscured their view.

In silence, they watched as the dust slowly cleared. They saw the helicopter on its side, about two hundred feet below the rim, resting precariously at the edge of a deep shelf below the crater wall, a rocky incline that sloped down to the lava lake.

“Somebody get on the radio,” Mac said, “and see if the dumb bastards are alive.”

Everyone in the room continued to stare at the monitors. Nothing happened right away; it was as if time had somehow stopped moving when the helicopter did. Then, as they watched, a few small boulders beneath the helicopter began to trickle down. The boulders splashed into the lava lake and disappeared below the molten surface.

More rocks clattered down the sloping crater wall, then more —larger rocks now —and then it became a landslide. The helicopter shifted and began to glide down with the rocks toward the hot lava. They all watched in horror as the helicopter continued its downward slide. Dust and steam obscured their view for a moment, and when it blew away, they could see the helicopter lying on its side, rotor blades bent against the rock, skids facing outward, about fifty feet above the lava.

Kenny said, “That’s scree. I don’t know how long it’ll hold.”

MacGregor nodded. Most of the crater was composed of ejecta from the volcano, pumice-like rocks and pebbles that were crumbly and treacherous underfoot, ready to collapse at any moment.

From across the room, Jenny said, “Mac? Hilo still has contact. They’re both alive. The cameraman’s hurt, but they’re alive.”

“How much daylight do we have left?” MacGregor asked her.

“An hour and a half at most.”

“Call Bill Kamoku, tell him to start his engine,” Mac said. “Call Hilo, tell them to close the area to all other aircraft. Call Kona, tell ’em the same thing. Meantime I need a pack and a rig and somebody to stand safety. You decide who. I’m out of here in five. We wait, they die.”

*****

The red HVO helicopter lifted off the observatory helipad and headed south. Directly in front of them, four miles away, they saw the black cone of Pu‘u‘ō‘ō, its thick fume cloud rising into the air.

Mac rechecked his equipment in his front seat, making sure he had everything. Jenny Kimura and Tim Kapaana were in the rear. Tim was the biggest of their field techs, a former semipro linebacker.

He stared out of the bubble. They were over the rift zone now, following a line of smoking cracks and small cinder cones inthe lava fields. The collapsed crater of Pu‘u‘ō‘ō was a mile ahead and just beyond it was the eastern lake.

Bill said, “Where do you want to put down?”

“South side is best.”

The helicopter set down about twenty yards from the crater rim. Immediately, the helicopter’s bubble clouded over with steam from nearby vents. MacGregor opened his door and felt air both wet and burning on his face.

“Can’t stay here, Mac,” Bill said. “I’ve got to move downslope.”

“Go ahead,” Mac said, then pulled off his headset and stepped down onto the gray-black lava without hesitation, ducking hishead beneath the spinning rotor blades.

The downed helicopter was at the opposite side of them, on a shelf above the lake. But its position was even more precarious now. The lava could spin at any moment, meaning the craft was perhaps seconds away from sliding down into the lava. Mac had already zipped up his green jumpsuit. He cinched the harness tighter around his waist and legs. He could loosen it when he got down there and put it around another person.

MacGregor handed the ends of the rope to Tim. He adjusted the radio headset over his ears, pulled the microphone alongside his cheek. Jenny had put on her own headset and clipped the transmitter to her belt, and she heard MacGregor say, “Here we go.” Jenny watched as Mac descended slowly and carefully into the crater.

The lava lake was nearly circular, its black crust broken by streaks of brighter and more incandescent red. Steam issued from at least a dozen vents in the rocks. The walls were sheer, the footing uncertain; Mac stumbled and slid as he went down.

Suddenly his extended leg hit a solid surface, like he was a base runner sliding into second.

Although he was only a few feet below the rim, he could feel the searing heat from the lake. The air shimmered unsteadily in the convection of rising currents. Between that and the sulfurous odors swirling from the crater, he began to feel slightly nauseated.

As Mac descended along the sheer wall, inside his heat-resistant jumpsuit, he was sweating. Thin Mylar-foam insulation sewn between layers of Gore-Tex kept sweat off the skin, because if the temperature went up suddenly, the sweat would turn to steam and scald his body, meaning almost certain death.

The helicopter hung only fifty yards above the lava lake. Below the crust, the glowing lava was around 1800 degrees Fahrenheit, and that was at the low end.

*****

“There’s a guy coming down for us.”

Pilot Jake Rogers, on his side and in a tremendous amount of pain, looked straight down at the lava lake and heard the hissing of the gas escaping from the glowing cracks. He saw spatters of lava, like glowing pancake batter, thrown up on the sides of the crater.

Jake didn’t think his leg was broken. The cameraman—Glenn something —was in worse shape, moaning in the back seat that his shoulder was dislocated. He rocked in pain, which rocked the helicopter. The sudden shift of weight sent the copter sliding downward again, throwing Jake’s head against the Plexiglas bubble.

The cameraman began to scream.

Only twenty yards away now, MacGregor watched helplessly as the helicopter began a rumbling descent. He heard yelling from inside, and it must have been the cameraman, because Jake Rogers swore at the guy and told him to shut the hell up. The helicopter slid another twenty feet toward the lava, then miraculously stopped again. The struts were still facing outward; the twisted rotors were buried in the scree. The passenger door was still facing upward.

*****

Jenny turned to Tim, covered her microphone, and said, “How long has he been down there?”

“Eighteen minutes.”

“He’s not wearing his mask. That may help him communicate clearly, but it’s going to get to him soon. We both know that.”

She meant the sulfur dioxide gas, which was concentrated near the lake. Sulfur dioxide combined with the layer of water on the surface of the lungs to form sulfuric acid. It was a hazard for anyone working around volcanoes.

“Mac?” she said. “Did you put your mask on?”

He didn’t answer.

She looked through the binoculars, saw that Mac was moving again. He was above the helicopter now, about to lean down on the bubble. She couldn’t see his face but saw straps across the back of his head, so at least he was wearing the mask.

She saw him drop to his knees and crawl gingerly onto the bubble. Mac picked up a short crowbar and started trying to pry open the door. He saw Jake pushing up on the Plexiglas from inside. He heard the cameraman whimpering. MacGregor strained against the crowbar, using all the leverage he had, until, with a metallic whang, the door sprang open wide and clanged hard against the side panel. MacGregor held his breath, praying that the helicopter wouldn’t begin to slide again.

It didn’t.

Jake Rogers stuck his head up through the open door. “I owe you, brah.”

“Yeah, brah, you do.” MacGregor reached out a hand, and the pilot grabbed it and clambered onto the bubble. Once he was out, MacGregor saw that his left pants leg was soaked in blood; it was smeared all over the Plexiglas dome.

MacGregor asked, “Can you walk?”

“Up there?” Jake pointed to the rim above. “Bet your ass.”

In the back, the photographer was huddled in a ball at the far side of the helicopter. Still whimpering. A haole guy, late twenties, skinny, his face the color of paste.

“He got a name?” Mac asked Jake.

“Glenn.” Jake was already starting up the slope.

“Glenn,” MacGregor said. “Look at me.”

The cameraman looked up at him with vacant eyes.

“I want you to stand up,” MacGregor said, “and take my hand.”

The cameraman started to stand, but as he did, the lava lake below began to burble, and a small fountain spit upward with a hiss. The cameraman collapsed back down and started to cry.

*****

Over the headset, Mac heard Jenny say, “Mac? You’ve now been down twenty-six minutes. Glenn and Jake already have pulmonary restriction. You’ve got to get out of there before you do.”

“I got this,” MacGregor said, looking at the lake through the bubble. Everything he’d learned from everywhere he’d been in the world of volcanoes told him he wasn’t fine at all.

“We’re gonna die here!” Glenn yelled, tears streaming down his cheeks.

“Just hang on,” Mac barked.

Then he climbed down into the helicopter.

The helicopter slowly rotated on its axis. Mac gripped the seat, trying to keep his balance, watching helplessly as the world outside spun, the Plexiglas bubble closer than ever to the glowing surface. Then it stopped, and the Plexiglas started to blister and melt, and smoke filled the interior of the helicopter.

“Just try to keep your balance so you don’t jar this thing,” Mac said.

The cameraman stepped between the seats, coughing because of the smoke, moving as if in a daze.

They were just a few feet above the lava lake. Small sparks were spattering up. MacGregor stepped out, drew Glenn after him.

He tried to ignore the smell of fuel.

Nearly out of time.

Glenn followed him outside.

“You got this,” Mac said, steadying him as his feet slid.

“I’m scared of heights,” Glenn said, keeping his eyes fixed on the rim of the crater, away from the lava.

MacGregor thought: You should have thought of that before, you jackhammer.

Mac looked up, saw Jake about ten yards above them, reaching for Tim. Down here, the sharp odor of aviation fuel was stronger than ever.

They kept moving. The guy looked around and said, “Hey, what’s that smell?”

Too late to lie to him, too close to the top. “Fuel,” John MacGregor said.

His radio crackled, and he heard Jenny say, “Mac, the lab says the concentration from the fuel vapor is going up.”

Mac looked back and saw the Plexiglas bubble of the helicopter had begun to burn; flames licked upward along the fuselage.

His headset crackled again. “Mac, you’re out of time—”

But in the very next moment Tim was grabbing Glenn in his big arms and pulling him over the side. He quickly did the same for Mac, who glanced back and saw the helicopter enveloped in flames. Glenn tried to move back to the crater, but Tim shoved him hard toward their copter.

“We’re safe now,” the cameraman said. “What’s the freaking rush?”

The helicopter exploded.

There was a roar, and the force of the explosion nearly knocked them all to the ground. A yellow-orange fireball burst up beyond the crater rim. A moment later, hot, sharp metal fragments clattered onto the slope all around them as they hurried to the red HVO helicopter.

•••

CHAPTERS 18–19

MacGregor said, “Are you going to tell me what all this is about?”

Colonel Briggs said, “It would be better if I showed you.”

The Military Reserve was built along the base of Mauna Kea mountain, Hawai‘i’s highest peak, which rose up to the north. Permanent structures were sparse: a small airstrip, a rickety wooden tower with flaking paint; a handful of Quonset huts streaked with red dust; a parking lot with cracked asphalt. The general impression was of desolation and neglect.

A camouflage jeep pulled onto the pad as the helicopter touched down. MacGregor and Briggs got in and were driven through the compound toward the mountain.

The driver was Sergeant Matthew Iona. Young guy, tall, skinny, a native, and dressed in fatigues. He said, “Dr. MacGregor, I need to know your glove and shoe size.”

MacGregor told him. Ahead was a small area surrounded by a rusted chain-link fence. The driver got out, unlocked the gate, opened it, drove through, locked it again behind them.

Directly ahead in the side of the mountain MacGregor saw a large steel door, ten feet high. The steel was painted brown to blend in with the mountain.

Briggs said, “That’s the old entrance. We won’t go in there. It’s no longer safe.”

“Why not?”

Briggs didn’t answer. The jeep abruptly turned left and went down a concrete ramp that took them twenty feet below ground level.

They pulled under a corrugated tin port alongside a small concrete bunker. The driver unlocked the bunker door, and they all went inside. There were bright yellow suits and gold helmets with glass plates hanging on the wall. Briggs pointed to one. “That’s yours.”

Briggs stripped to his underwear climbed into his suit, and zipped it up. Mac did the same. He remarked on how heavy the suit was.

“It is metal,” Briggs said, but he didn’t explain further.

The gold boots were also heavy. They attached with Velcro to the pants, which came down over them. Briggs told him to make the seal tight because it needed to be waterproof. Then

Briggs helped MacGregor put on the helmet. The glass faceplate was at least an inch thick.

“Now, let’s get going. It’s hot as hell in these things.” He went to a metal door at the end of the shed, punched in a code, and turned the handle. The door hissed open.

“This way,” Briggs said and led Mac into the darkness.

They were in a cave about twelve feet in diameter with smooth walls.

MacGregor said, “This is a lava tube.”

“We’ve always referred to it as the Ice Tube,” Briggs said. “At one time, it was cold enough to have ice on the walls in winter. Goes into the mountain about half a mile.”

During eruptions, lava flowed in channels down the flanks of the volcano. The surface of the lava flow cooled and formed a crust, while the lava below the hardened surface continued to flow. At the end of an eruption, the lava drained out, leaving empty tubes behind. Most lava tubes were only a few yards wide; some, though, were large caves. The HVO had mapped more than eighty tubes, and many of them were very deep.

Mac hadn’t known that this one, at the base of Mauna Kea, existed.

They went past massive air coolers with fans six feet in diameter. But John MacGregor could still feel the heat radiating from the depths ahead.

They were now walking on a metal deck covered in thick foam. On either side were stacked metal lockers, each four feet square and padlocked. Up ahead, pale blue light reflected off the ceiling.

MacGregor said, “What is this place?”

•••

CHAPTER 21

Huge white clouds blasted upward with a continuous, deafening roar. Standing by the giant circular steel vents, Oliver Cutler looked up to watch the steam clouds boil in the sky; his wife, Leah, was next to him. The camera guy and sound guy who frequently traveled with them, Tyler and Gordon, were a few yards away.

But the Cutlers had never required much direction from them; they had an instinct about the best way to be framed when they were staring down at another volcano. They were highly paid consultants, though their critics said the Cutlers’ real job was being famous.

Oliver and Leah Cutler were the husband-and-wife team chasing volcanoes, like the one in front of them.

“I’m ready for my close-up,” Leah Cutler said to her husband.

“You’ve been ready for your close-up your whole life,” Oliver said.

The ground beneath their feet vibrated even more powerfully. A louder rumbling filled the air. And as dangerous as they knew all this was, feeling the power of the volcano was part of the essential thrill of what they did; they felt a rush of excitement every time they showed up at a place like this.

And this volcano, one of twenty in Iceland, was relatively peaceful, though it had erupted in 2021 and 2022, filling the valley with blue-tinged volcanic gas.

Oliver’s cell phone rang. Even in the middle of the Icelandic countryside, cell phones worked. “Cutler.”

“Please hold for Henry Takayama.”

Now there’s a name from the past, Oliver Cutler thought.

He and Leah had met Tako Takayama five years earlier on a consulting visit to Hilo; Takayama, the head of Civil Defense, had invited them.

“Listen, I’m calling because I need your advice, Oliver. There’s something going on at the observatory, and I think it could mean big trouble.”

“Well, you know trouble’s our business,” Oliver Cutler said.

“I’m serious.”

“Actually, Tako, so am I.” Oliver winked at Leah and saw curiosity register on his wife’s face when she heard the name, obviously remembering him too.

“They’re predicting an eruption at Mauna Loa,” Takayama said.

“I figured that mountain was about due.”

“Yes, but there is some big operation up there and the army is heavily involved. All sorts of heavy equipment, helicopters, and earthmovers.”

“I’m listening.”

“They say all they’re doing is repairing the roads.”

Cutler considered that. Finally he said, “You know, they could be. I remember those roads, actually. The jeep trails have been bad for years.”

“So bad you need a hundred engineers and twenty helicopters up on the mountain? So bad you need to close the airspace for a week? Does that make any sense?”

“No, it does not.”

Even from across the world, Oliver could hear the concern in Takayama’s voice.

Cutler was trying to process what he’d been told and what he was intuiting. If Takayama was calling, he didn’t just have a problem with the army; he had a problem with HVO. And that likely meant a problem with MacGregor, the guy running it. That hothead. He didn’t know as much as he thought he did and, worse, didn’t know what he didn’t know. It had taken only one day in Hilo for Oliver and Leah to figure that out.

“So how can I help?” Cutler asked.

“I was wondering if maybe you could come for a visit.”

“Tako, that sounds like a marvelous idea, given where we are at the moment. But where we are at the moment is Iceland.”

“Oliver,” Takayama said. “I wouldn’t be calling you if this weren’t important to me. The city of Hilo has an interest in what’s going on. I’m afraid that interest is being neglected. There’ll be an eruption in a few days, which gives our city a perfectly legitimate reason to invite you and Leah here as official advisers.”

“I need to give you a heads-up on something before we go any further,” Cutler said. “We haven’t gotten any cheaper since we were last there.”

“I’ll pay the ransom,” Takayama said.

Oliver Cutler saw his wife smiling as she listened to his half of the conversation. She mouthed the word Aloha.

“How soon do you need us there?”

“How about yesterday?” Takayama said.

•••

CHAPTER 25

Everyone from HVO had been packed into the belly of one Chinook copter. Now they were all clustered around Kenny Wong’s laptop. Alongside it was the laptop belonging to one of the six young guys from the military base. It turned out these guys were part of a geophysical modeling team from AOC, Army Ordnance Corps. And, Kenny had to admit, they were damned good.

They had been to UH and reviewed Kenny’s stored data. They had run their own calculations on the data. And they seemed to have dozens of additional programs that they were running and rerunning on the spot.

Finally, the head of the team, a George Clooney look-alike named Morton, said, “I think we need to go outside now. All of us.”

Kenny, Rick, Mac, Jenny, Briggs, and the army guys all walked outside, shoes crunching on black lava. It was sunny up there at eleven thousand feet, with a light, fluffy cloud layer about five thousand feet below them.

“I’m sorry, boys,” Morton said, “but the stress-load calculations are very clear. Even if you have

magma within a kilometer of the surface—and most of it is much deeper than that—there is no way to open a one-kilometer vent in a mountain with conventional explosives. This mountain is too big; the forces are too big.”

Kenny said, “Even with resonant explosives?” Resonant explosives were a recent innovation. The

idea was to use small, precisely timed charges to set up resonant movement in large objects, the way giving small pushes to a swing gradually made it go higher and higher.

“Even resonant explosives won’t do it,” Morton said.

“Computer-controlled timing can produce very powerful effects. But we’re still orders of magnitude too small. Even if we wanted to go nuclear —and I’m going to assume we don’t —it probably wouldn’t be enough.”

No one spoke right away. The only sound was the wind.

During the discussion, something had nagged at Mac. He gazed at the summit now, shielding his eyes against the glare of the sun, looking past the engineers and Colonel Briggs and Jenny and the guys from the data room to where steam vents hissed into the air.

He had been thinking about steam all day.

Whenever the volcano began degassing, there was always the question of whether it was gas released by magma or groundwater being heated to steam. Steam eruptions had occurred on multiple occasions in the past, and Mac knew the dangers they presented, and not just to the environment.

“Hold on a minute,” he said.

They all turned to him.

“We’re thinking about this wrong,” Mac said.

Morton, who was standing next to Briggs, said, “How so?”

“We’re thinking about ways to control the volcano,” Mac said. “But we can’t.”

“Right,” Morton said. “We don’t have the explosive power to open a vent, and we can’t generate enough energy to do it.”

“But the volcano itself has plenty of energy,” Mac said.

He felt them all staring at him.

“What if we can make the volcano do the work for us?” Mac asked.

•••

CHAPTER 27

“You always want to be as close to the action as possible,” David Cruz said. “But any closer than this and it’s not safe.”

“Safe is no fun,” Rebecca Cruz said. She was standing in the huge upper parking lot of Ala Moana, staring up at the office tower Cruz Demolition was about to blow.

Go time, she told herself.

“Lock it and go off radio,” she said. “Let’s blow this puppy.”

She started counting backward to herself. Seven . . . six . . . five. . . four . . .

Rebecca waited, staring through the rain coming sideways now at the building.

At four seconds, she heard the preliminary crack-crack-crack-crack of the small calibration charges, the ones that thecomputer used. Ordinarily, it took the computer three seconds to make its final calculations.

Out loud, she said, “Three . . . two . . . one.”

She heard no detonation.

In fact, nothing happened.

The Kama Kai tower still stood in the slashing rain.

Rebecca began counting forward. “One . . . two . . . three . . .”

Still nothing.

Rebecca wasn’t a worrier. She was always too busy getting things done, basically.

But she was worrying now.

She had counted to twenty and still nothing had happened.

Of course the computer would take a certain amount of extra time to recalculate the blast timings because one side of the building was wet, and that changed the calibration impacts. But not twenty damn seconds.

She heard a soft whump!

Sawdust burst outward from the lower floors’ windows.

“All right!” she yelled, pumping her fist.

The walls of the upper stories gently folded inward. A perfect implosion; the building slid to the ground almost in slow motion. There was a final, much louder whump! as the roof crashed down.

And it was over.

Rebecca clicked her radio back on and waited for the congratulations from the others. Apparently, they hadn’t turned their radios on yet.

No matter. They would celebrate with beers very soon; she didn’t care how early it was.

As she turned to go find them, a dark brown van squealed to a stop in front of her, so close that it nearly clipped her.

Two men in dark raincoats jumped out. One of them said, “Rebecca Maria Cruz?” He held up some sort of badge.

“Yes.”

“Come with us, please.”

For one crazy moment she thought she was being arrested. Demolition without a license? But they didn’t touch her; they

just held open the door to the van.

“What is this?” she said.

Nobody answered.

She felt strong hands on her back, shoving her forward.

“Hey!” she yelled as she stumbled into a seat.

“Sorry, ma’am,” one of the men said. “We have a schedule.”

The door slammed shut, and the van shot off into the rain, tires squealing.

•••

CHAPTER 28

Hawaiian Volcano Observatory intern Lono Akani found the image he needed. In shades of purple, yellow, and green, it showed the summit crater and the northern rift zone curving off to the right. He zoomed in; the image softened and began to blur, but he saw the dark patches around the summit that indicated the air chambers.

He shipped it over to Rick and sat back, feeling the tension in his shoulders.

The intercom buzzed again. “Lono?”

“Yes, Rick.”

“Is this it? Just one?”

“That’s right,” Lono said. “Unless you want me to look farther back than —”

“No, no, it has to be recent.” Lono heard rustling papers, the soft murmur of other voices in the data room. Rick said to someone at his end, “Why don’t you show this to the army guys? I mean, they’re the ones that have to place the damn explosives.”

Then he spoke directly into the intercom. “Hey, Lono? Good job.”

And clicked off.

They’re the ones that have to place the damn explosives. Had he actually heard that right?

Lono wanted to open the intercom channel again. He knew there was an intercom built into the computer system that connected all the workstations at the observatory. There was also a

voice-recognition system that converted voice to text. It was old and outdated and not very good. Nobody used it much. But Lono knew it existed.

If he could just remember how to turn it on . . .

He poked around on the drive. Pretty soon he found it. A window came up; he typed in his password.

Rejected.

He glanced back at Betty. She was still going through her papers.

Lono typed in her name and password; he knew what it was because she always used the same one. The screen changed. It asked who to link to. He hesitated, then typed JK, for

Jenny Kimura, figuring she would be with Mac and not at her monitor.

He heard voices speaking and immediately clicked the button for text. His computer was silent. For a moment nothing happened, and then text began to flow.

KENSAY ***UP ***SO***

HAVE TO OPEN THE CHAMBERS IS THE

POINT AND YOU NEED AN EFFICIENT WAY

TO DO THAT

WE NEED FODAR MAPS TO DECIDE WHERE

TO OPEN UP

WHY

HOW MUCH EXPLOSIVE GOES IN EECH PIT

AN ARRAY IS TWENTY THOUSAND KEELOS

TIMES FOUR

THAT MUCH

ITS KNOT VERY MUCH WE WILL HAVE A

MILL YEN POUNDS OF EXPLOSIVE ON

THAT MOUNTUN IN THE NEXT TWO DAYS

BETTER YOU THAN ME

He signed off before Betty noticed what he had done, his mind racing as he tried to figure out why the army needed a million pounds of explosives to fix some bad roads.

As he was heading toward the main entrance to see if anything was going on outside, he heard a loud banging on the front door. One of the army guys opened it, and Lono saw a pretty, dark-haired woman wearing shorts and a T-shirt, hard hat under her arm, walk in like she owned the place. Two men, also carrying hard hats, were right behind her.

“Well, boys,” she said to the army guys, “looks like you got something you can’t handle and you had to ask for help.”

The army guys laughed and started shaking hands with the two men behind her. Everybody seemed to be old friends, acting like this was some kind of reunion.

This isn’t about roads, Lono thought. Definitely not about roads.

Then Lono heard the helicopter.

A few minutes later Lono saw Mac coming down the hall with an older, white-haired army man who looked like a commanding officer.

“Hey, Mac,” Lono said. “What the heck is going on?”

Mac did not seem pleased to see him. The army man looked even less pleased.

“Who the hell is this?” the army man said.

“You need to leave, Lono,” Mac said. “I’m suspending interns until further notice.”

Mac and the army man hurried away, leaving Lono standing there.

Lono was just a kid, but he knew when people were lying to his face. The story about roads was a crock. Why would Mac suspend interns at HVO without even giving a reason to the intern standing right in front of him?

Maybe the island wasn’t so safe after all.

•••

CHAPTER 36

A few hundred yards from the rim, Mac, Jenny, Iona, and Rick got out of the jeep. As soon as they stepped out, they felt the full force of the heat coming down the mountain at them. It was like an oven door had been flung open.

Rick Ozaki fixed his eyes on the summit. “You said Big Mauna was sending a message,” he said to Mac. “And I know what it is: You people get the hell off my island.”

They could hear the roar from inside the caldera. The earth suddenly shook with a harmonic tremor. Sometimes it was called a volcanic scream; it felt like the hum of a giant bass. They all held on to the jeep to keep from falling, and for a fleeting moment Mac worried that the jeep might tip over.

But the tremor passed.

“I thought I’d be used to the quakes by now,” Jenny said.

“Trust me,” Mac said. “You never get used to them.”

“To repeat the question Sergeant Iona asked a little while ago: Is this a good idea?”

“We’re fine,” Mac said, trying to sound more confident than he felt.

“Fine?” Rick said. “Check it out.” He pointed down at the wheels of the jeep at the same moment Mac smelled the burning rubber.

They all looked down and saw the wheels beginning to melt.

“Everybody, wait here,” Mac said. He jumped behind the wheel, gunned the engine, made a hard right turn, tires skidding as they spit up lava rock and dirt, drove the jeep back down the mountain.

He stopped at least a quarter of a mile below where he’d parked before, then ran hard toward them, leaning forward to take some of the steepness out of his climb.

“You guys ready?” Mac said when he was back with them, not even out of breath.

“Oh, hell no,” Rick said.

The heat became more intense the closer they got to the rim, as did the noise. Even Mac had never heard this part of the mountain so loud—it was as if the caldera had come to a full boil. They all had to shout to be heard above the din.

The heat became more suffocating as they made their way up through the rocks and brush. But Mac knew they needed to do this and do it now. The reality was that they were fast running out of time. Rick and Kenny and the rest of them could do all the projections they wanted about the rate of the rising magma. But John MacGregor was here because of what he considered the cardinal rule of his job: You had to be there.

They kept making their way through the rough terrain, the soil rich with iron and magnesium, the once green crystals of olivine transformed into the orange mineral known as iddingsite.

Most of the basalt rocks from previous eruptions were dark gray, sometimes black; some were a brighter rust color.

The closer they got to the rim, the more Mac wanted to stop and look around at this area so near the summit of the volcanic mountain that took up nearly half this island. He was overwhelmed as he always was by the thought of that, and by the reality of nature’s beauty, and its potential fury.

But the big clock kept counting down.

Mauna Loa had two rift zones, on its northeast and southwest.

Their group was on the northeast side today. There was no more conversation as they made their way the last fifty yards or so to the rim. The roar from the caldera had built up even more, and the sky had darkened somewhat, clouds lower than the top of

Mauna Loa.

“I’ve never heard it like this!” Jenny had to shout even though she was inches from Mac’s ear.

He was about to tell her that neither had he when he suddenly felt like his feet were on fire.

He looked down at his hiking boots and saw the thick soles with their wide treads were beginning to curl up and melt away, the way the tires of the jeep had a few minutes ago.

Mac saw Jenny and Rick and Iona staring down at their own boots, which were detaching at the soles. Rick Ozaki furiously stamped his feet on the ground and extracted from his pocket a roll of duct tape to repair his boots.

“That’s it!” Iona yelled. “I’ll see you guys back at the jeep.”

He stared hard at Mac. “You want to tell my bosses I deserted, go right ahead.”

He started back down the mountain.

Then the three of them were looking down at a lava lake, the heat shimmering off the silver surface.

“This lake . . . it’s new, right?” Jenny yelled to Mac.

Mac nodded. The opening of a new lava lake near the northeast summit confirmed that the lava would head in the direction of Mauna Kea and the Military Reserve.

On the other side of the lake, small amounts of lava were pushing through cracks, and tiny geysers shot lava toward the sky.

“Mac,” Rick yelled, “we need to get out of here or we’re going to be walking barefoot on hot coals back to the jeep.”

“Gimme one more minute,” Mac said, taking out his cell phone. “I need to take some pictures.”

“For what?” Rick said. “The top of your casket?”

Then he watched as Mac scrambled up and over the rim.

•••

CHAPTER 39

General Mark Rivers, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, had been appointed by the previous president and stayed on when his successor took office. Rivers had offered to step down; the new president had refused to accept his resignation. That was partly due to his competency but mostly due to his popularity, not just with all branches of the armed forces but with the public. Rivers was being considered for a fifth star because of his leadership in both Iraq wars and in Afghanistan.

The current president had joked, more than once, that he served at the pleasure of General Rivers, not the other way around.

Rivers was six feet six inches tall and had the silver hair and rugged good looks of the actor Pierce Brosnan. He had been a star tight end at the United States Military Academy and had risen through the ranks to become the youngest army chief of staff; before that, he had been the youngest commander of Central Command in army history. It was widely assumed in his party’s political circles that if he wanted to run for president when the man presently occupying the Oval Office concluded his second term, the nomination was his.

He was as comfortable in the field as he was on the Sunday-morning talk shows, and he dominated any setting in which he found himself. That included the Oval Office.

Now he was seated at the head of a long table on the second floor of the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory in the largest and most private conference room the place had. He was in full uniform, despite the heat outside. Colonel Briggs sat to his right, Sergeant Matthew Iona next to Briggs. Rebecca Cruz was the only one in the room representing Cruz Demolition. Mac had Jenny and Rick Ozaki with him.

Oliver and Leah Cutler with Henry Takayama between them were at the far end of the table, across from Rivers. Mac and Oliver Cutler had barely nodded at each other.

“I just want to make something clear before we start,” Rivers said. “I’m aware that I’m going to be presented with three plans for dealing with our problem. I could have asked for written proposals, but I don’t operate that way and never have. I like to look people in the eye. It’s why I’m here. And I’m sure as hell not walking out of here without a plan.”

Mac looked around. General Mark Rivers had everybody’s complete attention.

“There’s an old army expression about success not being final and failure not being fatal,” Rivers said. “But this time it might be.” Rivers crossed his arms and leaned back slightly in his chair.

“Welcome to the dream team,” he said.